How ‘Silent Hill 2’ became the horror game with one of the highest replay values

Horror is one of the most popular genres of fiction around, with films, books, poetry and the like supplying us with endless nightmare fuel. We love the thrill of being scared because we know we’re still the ones in control—it’s all fake in the end, which makes us feel safe enough to ignore our physiological flight or fight reaction. That’s why horror games have been so popular in the past too, with memorable franchises such as Resident Evil and Amnesia, and even some non-horror titles bringing their own brand of spooks to the table. But one series, for a time, stood above all else when it came to just how scary a game could be: Silent Hill.

While the first game’s signature thick fog came as a happy accident after the developers were trying to remedy hardware limitations, it was 2001’s Silent Hill 2 (SH2) that really stuck in fans’ minds, leading it to being widely considered as the best one out of the series due to its harrowing story and, most importantly, the way it deals with self-reflection and trauma. But in order to truly understand the perfectly-crafted terror of SH2, we must go back in time first. History lesson, anyone?

What is 'Silent Hill'?

Silent Hill was first released for the PlayStation 1 (PS1) by Konami all the way back in 1999, three years after the release of Capcom’s mega success, Resident Evil. From then on, the two were considered rivals in the survival horror game genre. To put it simply, each Silent Hill game features a protagonist who—knowingly or unknowingly—has a connection to the fictional American town of Silent Hill. They are instinctively drawn to it, and once there, are forced to face their darkest secrets and confront the sins of their past.

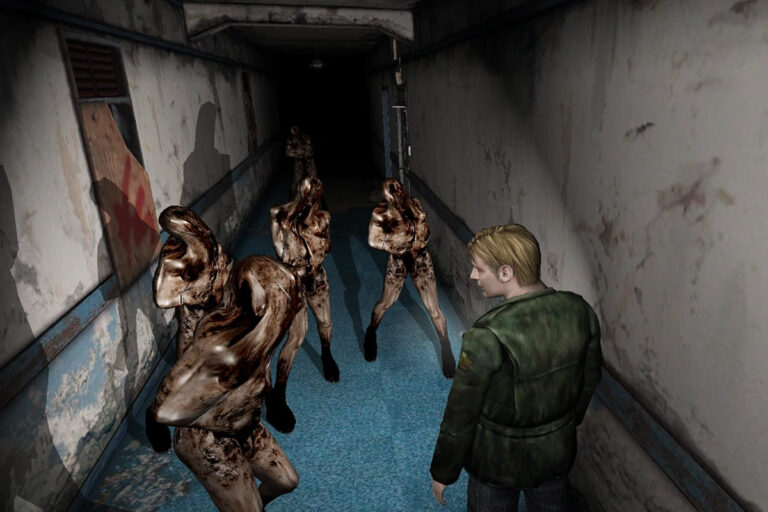

What starts out as a romp through a fairly ordinary, if creepy town, soon turns into a nightmarish bid for survival as it periodically transforms into the ‘Otherworld’, a demonic and twisted version of Silent Hill filled with creatures so violent and disturbing they’ll leave you with nightmares for weeks. The story goes that many years ago, the Otherworld was created by a cult that still secretly operates within the town. It is here that protagonists must face their demons and uncover the truth of why they were drawn to Silent Hill in the first place.

Many fright fanatics consider Silent Hill as the stronger series when compared to Resident Evil due to the fact that, as the games progressed, the latter became more action-focused and lost its horror edge. As time went on however, the roles suddenly got reversed—Resident Evil went back to its horror roots and Silent Hill began to lose its way. Titles such as Silent Hill: Homecoming and Silent Hill: Downpour just didn’t have what the first four prior games did. As much as it hurts to admit, the once great horror franchise has now disappeared into the ether, with no new entry since 2012.

However in 2014, a glimmer of hope appeared for the series in the form of a demo called P.T (meaning playable trailer). It was released on the PlayStation store and was confirmed to be a new Silent Hill title named Silent Hills to be headed by Hideo Kojima of Kojima Productions with the aid of horror legend Guillermo del Toro and The Walking Dead actor Norman Reedus.

Sadly, only a year after, Del Toro announced that he would no longer be a part of the project, presumably because of Kojima’s departure from Konami. Just days later, P.T was officially cancelled and the demo pulled from the PlayStation store, leaving many fans angry and inconsolable. There has been no news of a new Silent Hill title since then.

Trauma and self-reflection

Now that you’re up to speed, let’s move on to the topic at hand: SH2, and how it accurately portrays the self-reflection and trauma of protagonist, James Sunderland.

SCREENSHOT recently spoke to Silent Hill fanatic Konstantin Kunow, who shared his vast knowledge about the way the game uses symbolism to illustrate Sunderland’s trauma and inner feelings.

At the very beginning of the game, we are introduced to Sunderland, a widower who travelled to Silent Hill after receiving a letter from his late wife Mary, who he lost to a violent and mysterious illness, telling him that she is waiting for him there. Spooky, indeed.

A little further in, Sunderland discovers a radio which is spewing out static—Kunow believes this to be our first encounter with the game’s symbolism. “One of the first hints we get is the radio at the beginning, where we hear Mary’s voice for the first time,” he explained. “Her words are constantly disrupted by the radio static, but if you listen closely you can hear her asking why he killed her.”

After this unnerving scene, our protagonist is confronted with his first monster: a Lying Figure. Their whole bodies are encased in a straitjacket of flesh, with tell-tale female legs and are wearing what looks like a pair of high heel shoes wrapped in flesh. While quite a common enemy, they are an important one, as Kunow pointed out, “The Lying Figures symbolise Mary and James’ helplessness during the disease.”

These disturbing creatures attack by essentially throwing up on Sunderland, and if we stick with the idea that they represent Mary, then, as Kunow puts it, they are “also her lashing out towards James with words full of hate.”

“It also resembles James’ disgust towards Mary,” Kunow added, referencing one of the game’s cutscenes where Sunderland’s dead wife can be heard saying “I look like a monster.”

The first Lying Figure is stood next to a corpse which looks suspiciously like Sunderland, and although it’s not hostile, it stirs something in Sunderland which triggers him into killing the monster. Given what we’ve just discussed, I think you can see what’s happening here…

As you progress through the game and start to uncover Sunderland’s backstory, you realise that the town, and therefore its monsters, are trying to guide him towards the truth that he has tried so hard to repress.

“Most of the time, it’s subjective,” Kunow told us. “The Otherworld hospital, with its walls covered in dirty blankets, resembling Mary’s rotting skin, confronts James with his sin of being disgusted by his weak and lonely wife.”

However, the game doesn’t freely give this information to Sunderland, nor the player. As he fails to get the hints provided to him, the town seems to become more and more desperate to convince him of his guilt and traumatic past. One of the best examples is with the character of Maria. “James is forced to experience the death of Mary again and again by [the town] letting him see a reflection of her in the form of Maria being killed by Pyramid Head over and over again.”

“After this, the town even directly accuses him in Neely’s bar, telling him he should die and that he would go to hell,” Kunow added.

Our game expert believes that, overall, Silent Hill wants to support Sunderland and wants him to find the truth, albeit in a twisted and depraved way. “A good example for that is Pyramid Head,” he added.

Pyramid Head is probably one of the most iconic horror monsters out there—with a massive metal pyramid-shaped object on its head, a giant rusty sword and a skirt made of skin, it is the manifestation of Sunderland’s wish to be punished for Mary’s death. Who knew, heh?

“Throughout the whole game, Pyramid Head is semi-hostile towards him [James]. Sure, he can kill James, but most of the time he kind of guides him through the town,” explained Kunow. “In the first level he paves the way for James to continue, or in the hospital where he kicks him off the roof, allowing the protagonist to get to a room he couldn’t access before.”

Does ‘SH2’ convey the trauma portrayed well?

While all the symbolism is there and extremely prominent throughout the game, it does beg the question, how does all this translate to the player? Is it obvious that this is about Sunderland’s trauma? Kunow believes it does.

“I think SH2 displays trauma in a very unique kind of way—a kind of ‘show, don’t tell’ way. The only way you can understand the story is by observing and interacting with the environments and witnessing James’ reactions to them.”

And this is what makes the game so enjoyable. It doesn’t hand players everything they need on a plate. Instead, it makes you work for it, guides you when needed but never gives up its secrets readily either. Even after two or three playthroughs, there still might be parts that you missed previously and are just beginning to understand.

“You are forced to decipher the gruesome hints the town gives you, which is very unsettling but intriguing at the same time. I personally think that’s brilliant […] but it requires the ambition of the player to go for the truth.”

So, in essence, yes, the themes do translate over, but only if you are willing to work for that understanding—much like how The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask deals with the different stages of grief. Overall, Silent Hill 2 gets all the horror elements right, but it also nails something that a lot of games since have fallen short of: story. Not only does it bring the scares, but it also brings a sense of intrigue and mystery while telling the heartbreaking story of a man coming to terms with the atrocities he has committed against the one person he loved more than anything in the world.

21 years after its release, SH2 still has so much to give. It will scare you half to death and make you cry even harder—something that a lot of AAA horror games fall short of these days. One thing is for sure though, Silent Hill may have lost its way, but the stories the series has told will stay with us forever.