Chemotherapy-induced hair loss might soon become a thing of the past, thanks to Luminate Medical

Hair loss is one of the most recognisable side effects of chemotherapy affecting millions of cancer patients annually. With 47 per cent of female patients considering hair loss to be the most traumatic aspect of chemotherapy and 8 per cent of them declining the entire treatment for fear of hair loss, Luminate Medical is dedicating itself to provide a patient-focused alternative—thereby uprooting all visible connections of the side effect from the treatment.

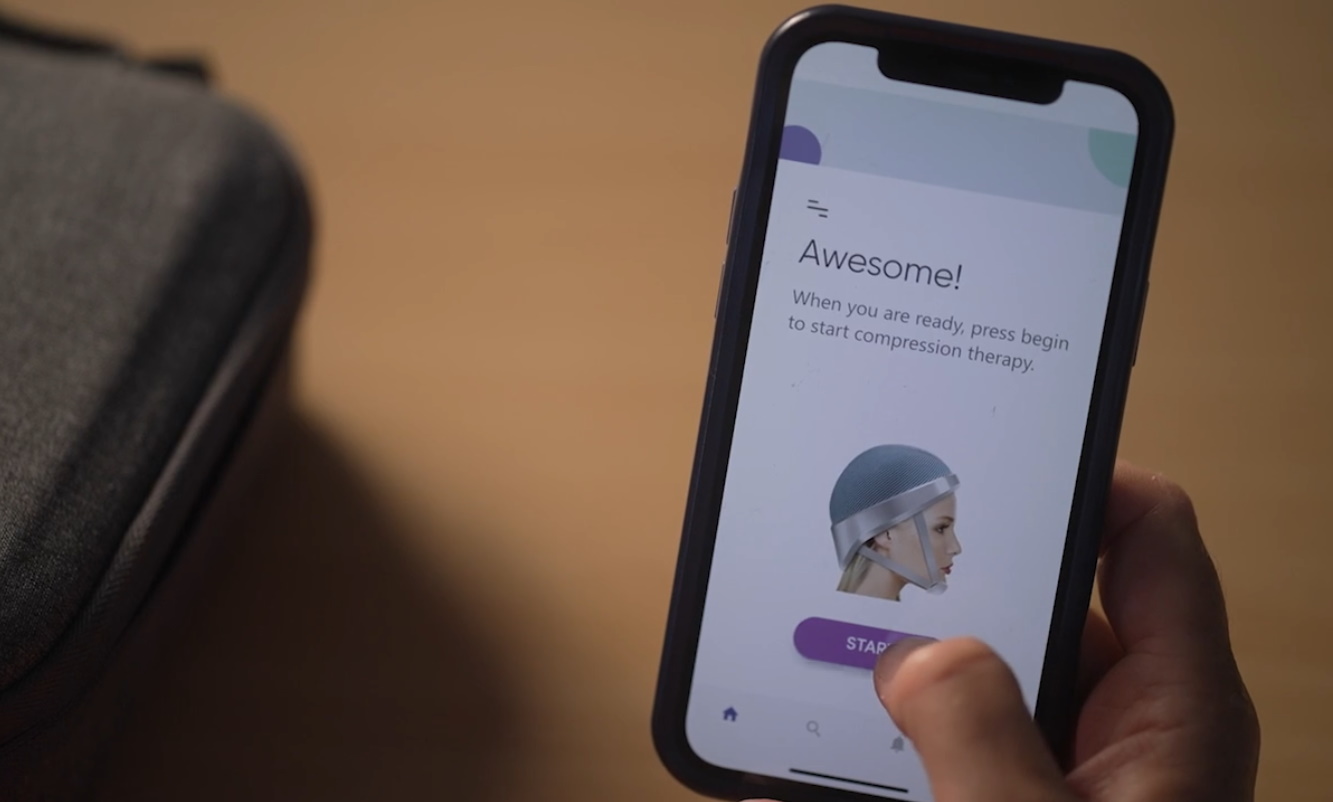

Co-founded by Aaron Hannon and Doctor Bárbara Oliveira, Luminate Medical’s groundbreaking venture (dubbed LILY) is a wearable device that will use electrical stimulation to curb the visible side effect. When a patient undergoes chemotherapy, the cancer-inhibiting drugs courses through their entire body—travelling absolutely everywhere blood does. This, in turn, results in a variety of side effects like weakness and nausea, along with significant hair loss when the substances affect follicles in the long run. Developed in collaboration with the Translational Medical Device Lab at the National University of Ireland, Galway, Luminate Medical’s solution is to prevent blood from reaching those cells in the first place.

The portable device works as a mechanised compression garment for the head using soft materials to achieve the pressure. According to Hannon, the device is therefore comfortable with the pressure being carefully monitored. There’s also no risk of damage from the lack of blood flow in those cells.

“Compression therapy has been really well studied,” he said in an interview with TechCrunch. “There are years of literature around how long you can apply these therapies without damaging the cells. There’s a certain amount of mechanical engineering involved in making it both comfortable and effective.”

Patients are required to wear the cap during and after the entire chemo session. By restricting blood flow to the skin of the scalp, the novel device facilitates the flow of the drugs to the intended tumor or cancer site while saving hair follicles from damage. To date, Luminate Medical has performed animal trials—which saw strong hair retention of around 80 per cent with no adverse effects. Although full-fledged human trials require more time and approval to set up, initial tests of the wearable devices’ effects on healthy patients have proven to work exactly as expected on humans.

“We’re really excited about the efficacy of this therapy because it works with lots of hair types,” Hannon said—highlighting inclusivity as an important yet underestimated factor when it comes to innovations in healthcare. The company also backs the belief that no patient should have to compromise their identity to get the best available medical treatment. “Luminate Medical recognises that hair is an essential element of personality and self-esteem, and is dedicated to using the latest advances in medical technology to protect this,” the company website reads.

When it comes to competition, Hannon noted the presence of new treatments that cool the scalp instead of compressing it. However, the CEO added how patients predominantly engage in the purchase of wigs to counter the side effect. Given the fact that wigs are covered and hair loss is considered a medical condition by many insurance companies and other methods of reimbursement, TechCrunch noted how it will take time and evidence to get the device approved for those processes.

The team, however, is confident that the solution—valued at around $1,500—is within the means of many as long as other costs are being picked up by insurance coverage. After all, people spend fortunes on wigs and other hair retention products and methods. Who wouldn’t prefer prevention over cure in the first place? Luminate Medical is also seeking to offer the benefits of the device to those who can’t afford the cost out of pocket—therefore progressing toward FDA approval and a US launch with Europe and others to come. At the moment, the team is focused on getting the device into the hands (and onto the heads) of its first set of patients.