Opinion

What is e-waste and how will mobile phone recycling work for you?

By Emma O'Regan-Reidy

Opinion

What is e-waste and how will mobile phone recycling work for you?

By Emma O'Regan-Reidy

Updated May 18, 2020 at 04:59 PM

Reading time: 3 minutes

Climate change

Apr 9, 2020

The origins and afterlife of our electronics are rarely questioned. iPhones and Macbooks seem like organic features of any Apple store, sprouting from the pine tables in the Covent Garden location. Coffee machines, toasters, and portable speakers are all extensions of our domestic space; easily picked up from an Argos and easily replaced. What we seem to completely forget about is the part those electronic devices play in global warming and the e-waste they represent.

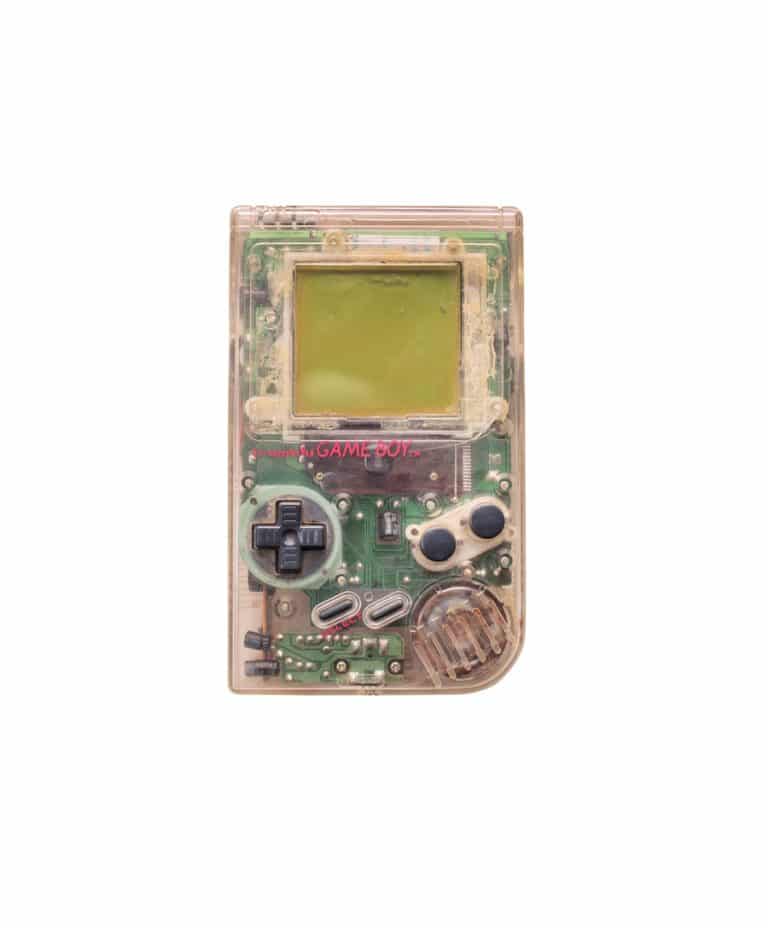

The general consumer hardly ever sees the internal circuit boards composed of heavy metals such as mercury, lead or cadmium which, if not properly disposed of, contaminate ecosystems and nervous systems of those exposed to the products. As one of the largest global consumers of electronics per individual, the UK plays an integral role in e-waste disposal. The country’s facilities, however, often miss the mark.

Once our phones die, most of us don’t think ‘Where should I sell my phone?’ but instead wonder if it’s okay to just throw it in the bin. According to the Financial Times in What happens to your old laptop? The growing problem of e-waste, the amount of e-waste produced per person in the UK in 2016 was around 24.9 kg. To put this into perspective, only 6.1 kg was produced per person on a global scale. In the UK, most e-waste is unlikely to be recycled. Following an investigation in 2019 by the NGO Basel Action Network (BAN), it was discovered that the UK is the worst offender in Europe for illegal e-waste exports to developing countries who are even less equipped to deal with this abundant and harmful waste.

While 1.2 tonnes of electrical devices were sold in the UK in 2018, only 500,000 tonnes of those devices made it to recycling centres. This statistic could be slightly skewed, as some of that remaining amount could be ascribed to people keeping their devices for longer than a year. Yet, it reflects the unbalance between consumption and recycling rates.

Many countries in the EU operate through a system where electronic retailers must take back older products from past customers. However, the rise of online shops has made this harder to enforce. Even if disposed, electronic items do make it to the e-waste processing centre, such as the Veolia one in Southwark, many facilities aren’t equipped to fully process the product into its core metals. After taking apart the old hairdryers, keyboards or iPods, these parts have to be shipped to other processing plants in order to recycle them completely.

Although there have been measures to reduce the steps involved in e-waste processing, such as New York implementing Recycle Track Systems (RTS), this issue could be solved partially by having less e-waste to deal with in the first place. Electronics companies could reduce the current amount of e-waste by providing more detailed instructions as well as continuing to manufacture parts for their products after they’re distributed in case customers decide to repair their products locally.

I became aware of the realities of electronic recycling after attending a lecture given by visual artist Jen Liu on her endeavours to better understand these issues, particularly in China. Liu’s practice focuses on the often hidden production and consumption lines attached to everyday technologies. By exploring labour rights, Liu uncovers the biological and emotional impacts of work dealing with the physicality of these technologies. By displaying archival photos of Japan in the 1960s, Liu confronted the audience with the brutal realities of chemical poisoning as a result of producing or recycling technology.

The particular disease of ‘itai itai’, which served as a prominent reference for Liu’s artwork, causes the bones to become soft. The poisoned body then curls in on itself, as its bones crush under its own weight. Liu commented that the body exposed to chemicals like cadmium and lithium replicates through this painful curling motion the disjointed circular economy of recycling which it’s a part of.

The toll on the worker’s body reflected by ‘itai itai’ is similar to the current illegal shipments from Europe to other nations such as Nigeria, Tanzania and Pakistan. Jim Puckett, director of BAN, observed that these shipments “perpetuated an EU waste management regime ‘on the backs of the poor and vulnerable’.”

Exhibited at the Singapore Biennale last year, Liu’s multimedia work Pink Slime Caesar Shift: Gold Edition incorporates concentric golden circles to further evoke this unfortunate reality. Shiny 3D orbs bounce along the space of a computer-generated laboratory as an instrumental cover of ‘Bang Bang’ by Ariana Grande, Jessie J, and Nicki Minaj loops in the digital space. Similarly shaped to the curled, poisoned bodies of 20th century Japanese e-waste workers, the chemical properties of the recycled metals are transformed through these animated gold particles.

When asked by a student in the lecture’s audience if any significant political or social change had occurred as a result of her work, Liu responded: “honestly, no.” Her answer prompted a discussion of the importance of art to elicit awareness not present previously. Liu’s honesty serves as an encouraging reminder in times when participating in the art world at any capacity feels cyclical; perhaps especially so in our current global situation. Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, most countries have put their recycling systems on hold.

The US and UK, along with many other nations in the west, have deemed only scrap recycling an important link to the supply chain and therefore remain open as usual. The pandemic has allowed our planet to catch its breath due to the immense reduction in human pollution during these first few quarantined months of 2020. However, as everyone is now more plugged into their technologies out of oscillating necessity and boredom, perhaps this is the opportune moment to reflect on the physical realities of our digital devices.