Mastercard is using card expiration dates as a tool to raise awareness against wildlife extinction

The Earth has experienced five mass extinctions to date, each accounting for a loss of more than 70 per cent of all species on the planet. While the most recent one was 66 million years ago, scientists are now concluding that humanity is undeniably on the path to a sixth major extinction. At a time where more than 37,400 species are threatened with extinction, Mastercard has joined forces with Conservation International to introduce a line of ‘Wildlife Impact Cards’ with the aim of promoting a sense of urgency and call to action with its expiry date.

What is a Wildlife Impact Card and how is it designed to raise awareness?

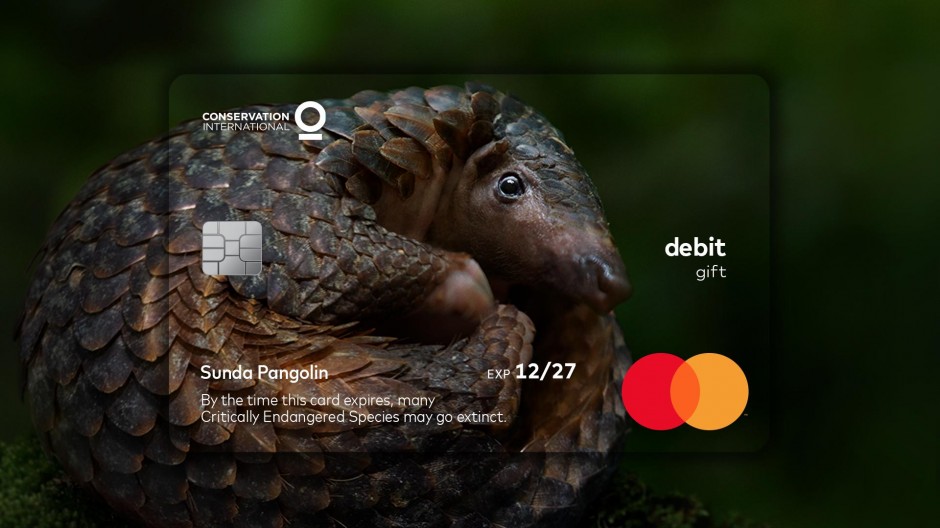

Mastercard’s Wildlife Impact Card is essentially a gift card that can be sent to your loved ones and be used everywhere Debit Mastercard is accepted. Available in four types, each card features an endangered species—the African forest elephant, black-and-white ruffed lemur, Peruvian yellow-tailed woolly monkey and the Sunda pangolin. Just like every other debit and credit card, these cards are also printed with an expiry date. But by the time a Wildlife Impact Card expires, so will the endangered species featured on it.

For example, the African forest elephant, a highly intelligent species that has suffered a population decline of 86 per cent over the last 31 years, is predicted to reach mass extinction by 2028. The card featuring the species is set to expire in 2028 as well. In the case of Sunda pangolins, the most trafficked mammal in the world suffering a global population decline of 80 per cent, the species is said to expire in 2027. So is the card featuring the endangered species.

“As a company committed to fostering a sustainable future for all, we believe an important aspect of that is to protect Critically Endangered species and the habitats in which they live,” said Raja Rajamannar, Chief Marketing and Communications Officer of Mastercard, in a press release. “Through our strong partnership with Conservation International—one of the world’s leading conservation organisations—we’ve created a way to connect consumers to their passion for wildlife and the natural world, enabling them to contribute and make an impact.”

By linking a tangible expiry date to four critically endangered species, Mastercard essentially highlights how short the time frame is for protecting these animals from extinction. Apart from prompting a call to action, Mastercard also donates $1 for every gift card purchased to Conservation International to help support endangered species and their habitats—including priority areas equal to 40 million hectares of landscape and 4.5 million square kilometers of seascape globally by 2030.

Currently available as virtual cards which can be used to shop online or add to mobile wallets for in-store purchases, Wildlife Impact Cards will soon roll out as physical ones—made of eco-friendly material to keep expired cards from contributing to plastic pollution.

Consumption habits as a trigger for rapid extinction

Although Mastercard’s partnership with Conservation International—along with the introduction of Wildlife Impact Cards—are necessary steps towards a hopeful future, it also opens up the conversation about how our consumption habits are triggering rapid extinction. Trend Watching, for example, highlighted how a Wildlife Impact Card can be used by a consumer to purchase products contributing to the extinction of an endangered species in the first place.

Our own consumption choices are in fact credited as a major factor driving biodiversity loss. It is also speculated that we would need nearly three Earth-sized planets to support such habits on a wider scale. In the case of Wildlife Impact Cards, consumers are essentially gifting this exploitative purchasing power to others. Now, one thing to note here is how we were previously blaming and waiting around for companies to alter their business models to better suit this cause. Among that push, however, we seem to have successfully turned a blind eye towards our personal consumption patterns.

While various companies like Mastercard are catching on and actively committing themselves to the cause, they have little to no control over our choices. This ultimately drives their efforts into a dead end—unless we initiate conscious choices for both ourselves and the planet. With that being said, here are a few lifestyle changes you can make today to secure a better tomorrow:

1. Eat consciously

How can you eat consciously without harming wildlife, you ask? ‘Go meatless!’ is the typical solution this narrative is boxed into, given how industrial meat production accounts for 45 per cent of the heat-trapping greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere caused by deforestation. But deforestation is not the only source of greenhouse gas emissions involved with meat production. The amount of fossil fuels used to produce feed for animals is one of the major reasons that make meat one of the most environmentally destructive foods you can eat.

In the US, it takes around 25 kilograms of grain to produce one kilogram of beef. This grain-to-meat ratio for pigs is 9:1 while chickens are at 3:1. “Imagine throwing away 25 plates of perfectly good food to get one plate of beef,” The Conversation summed up, regarding the demand for resource-intensive meat. One simple step to take in this regard is to cut out the ‘grain-fed beef’ altogether from your diet.

2. Shop consciously

The root of major consumer goods triggering wildlife endangerment can be traced back to palm oil. Endangering the Sumatran tiger as well as the Sumatran and Bornean orangutan, palm oil production is responsible for the destruction of 300 football fields worth of forest every hour. With every lipstick and laundry detergent you purchase from brands that source palm oil via unsustainable means, you are essentially helping fund worldwide deforestation and mass extinction efforts. It is therefore important to be wary of your purchases in order to prevent the addition of more species into the list endangered by palm oil production. Palm oil-free alternatives are further suggestions in this regard. It also helps to stay in the loop with the list of pseudonyms brands use to market products that use palm oil.

3. Support the cause

Once you’ve tweaked your lifestyle, it is also important to be proactive towards the cause and help spread the word yourself. Encourage others to start making conscious consumption choices and support the organisations who have already pledged themselves to reverse its effects. A donation, be it time or financial, often goes a long way if you are committed to making a change today.

A research by Cone Communications highlighted how 90 per cent of gen Zers stand ready to take action against various social and environmental issues. The ideal way forward, targeting this upcoming consumer base, can probably be an app that alerts credit and debit cardholders whenever they’ve made a purchase that contributes to endangering wildlife species. Until then, let’s pledge our lives to make conscious choices and “start something priceless” with innovations like the Wildlife Impact Card.