How a trending hashtag brought awareness and exploited the Sudan crisis

You may have seen the hashtag #BlueforSudan trending on Instagram and Twitter, or perhaps you’ve seen people changing their profile photos to the colour blue. Sudan was in a blackout, while the world watched.

Earlier this month, Sudan’s military leaders have reached an agreement with the opposition alliance to share power until elections can be held. Until then, however, the country has faced deadly political unrest and since the military ousted President Omar al-Bashir in April, Sudan has been in turmoil. On 3 June 2019, what started as a peaceful protest resulted in the Khartoum Massacre (over 100 people killed and 70 raped). The internet in the country was almost completely cut off and censored, not only making it difficult to estimate the exact number of people killed and injured, but also making it almost impossible for the people of Sudan to share the hardships they were facing. Internet access has only been partially restored this week.

When an entire country has no means of communication to the rest of the world, and when every piece of information is censored, this inevitably leads to a delay in precise reportage from global news and media outlets. In this particular case, when the world failed to immediately report on a major crisis, social media used its power to take this story and make it go viral. If you’ve wondered why everyone’s Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter accounts suddenly turned blue, this was to pay tribute to all those who died in the disputes—including 26-year-old Mohammad Mattar, who was killed in the Khartoum Massacre. At the time of his death, Mattar’s profile picture was blue, what soon became a symbol of solidarity with Sudan.

Suddenly, the hashtags #BlueforSudan, #Sudan and #TurnTheWorldBlue all went viral, urging Western media and people to pay attention to the conflict happening. Sudanese New York-based beauty and lifestyle influencer Shahd Khidir played an active part in raising acknowledgement for this by using her platform. She has posted a powerful photo of herself crying, asking everyone to raise awareness and share on the atrocities happening—having to break from her regular scheduled brand posts. Speaking to Screen Shot about how brands have reacted to this, Shahd says that while some were understanding, others pulled out of campaigns not wanting to work with her again—”But I am not upset it was important for me to raise awareness about the Sudan revolution and in essence I don’t really need to do business with brands that don’t support me”. Shahd has taken on the role of a reporter to speak out on these issues when the civilians in Sudan had no way of doing so. Through her persistence and determination, she spoke for those who couldn’t have a voice.

“I definitely feel that social media has been effective in the Sudanese revolution”, says Daad. Daad, a make-up artist and beauty influencer from New York is also one of the Instagram personas whose activism was prominent in bringing recognition and believes that social awareness impacts and educates the public. It’s also important to note that social media bringing awareness also leads to the donations of funds and resources.

But whose responsibility is it really to share and raise awareness? Most importantly, as social media users, we are often judged for being too political or not enough. In that light, do we owe it to always use our voice, no matter how big or small? Selective empathy comes to mind. The immediate reaction to the Notre Dame fire was, rightfully, heavily criticised and compared to the Sudanese crisis. Yet, the most difficult aspect of this all is the fact that politicians all over the world shared messages of solidarity for a building but failed to do so for citizens of a suffering country. And, if we must choose somebody to blame for the lack of awareness, who better than those paid to stay on top of current affairs but who decide that these issues are not significant enough to report on?

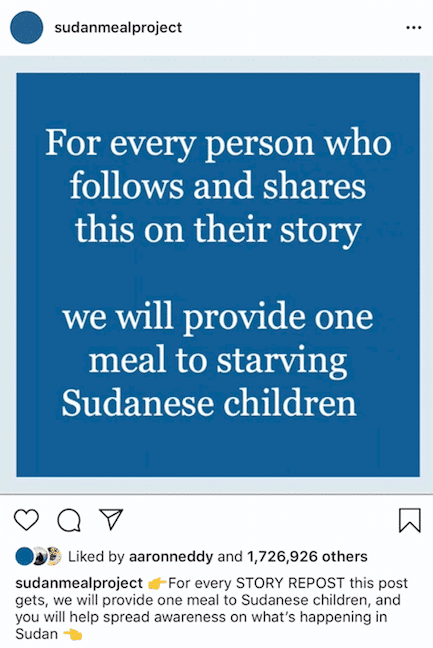

As this is the internet after all, when a story begins to circulate on a scale as large as #blueforSudan, trolling, fake news and exploitation is inevitable. By now, you must have seen clickbait posts on your social media, promising that for every follow, like or repost, a meal would be provided for the “starving Sudanese children”. The now-deleted Instagram account @sudanmealproject managed to gain over 1.7 million likes on such a post. While we question how 1.7 million users fell for this idea, we also need to question the logistics of this and how a like can provide physical resources needed to help. Newsflash—it cannot.

How do Instagram accounts such as @sudanmealproject benefit from this? @exposinginstascams is an Instagram account that sheds light on fake news and accounts circulating on the platform. It has successfully exposed accounts attempting to exploit the Sudan crisis. Screen Shot spoke to the 14-year-old account owner—preferring to remain anonymous— who managed to get @sudanmealproject to confess that their intentions are certainly not in Sudan’s best interest, but for self-profit. “Lots of people changed their profile picture to blue to raise awareness, but they didn’t understand they weren’t really helping”, said the @exposinginstascams account-owner, adding that others were just trying “to gain followers and likes”. With substantial engagement, these accounts can gain from advertising and selling on their account. And unfortunately, it doesn’t end here. Just type in ‘Sudan’ and ‘meals’ into your search engines on Instagram and look at how many accounts come up.

Social media has helped bring awareness to the conflict in Sudan. It also presented us with fake news and fake charities trying to benefit from this, which took away credibility from the real issue. “I think that some people are always going to be opportunists and there’s not much we can do but remain concentrated on the bigger picture”, says Daad. And since it is impossible to put an end to the exploitation of people in crisis, we must remain focused on the mission of helping wherever we can.

Sometimes it takes a little more than updating our profile photos or Facebook statuses, but we can use our platforms for the greater good when needed, the same way millions of Instagram users have managed to help bring awareness to Sudan.