Cuttlefish are able to remember their last meal. Three-second memory, who?

Do you remember your last meal? Okay, maybe you can. But what about your lunch last Wednesday? Chances are you probably can’t. That’s because our episodic memory has been shown to deteriorate over time. Surely other animals are the same, right? Well, think again—recent research from the University of Cambridge confirms that cuttlefish can. It’s about time we drop the ‘three-second memory’ stereotype.

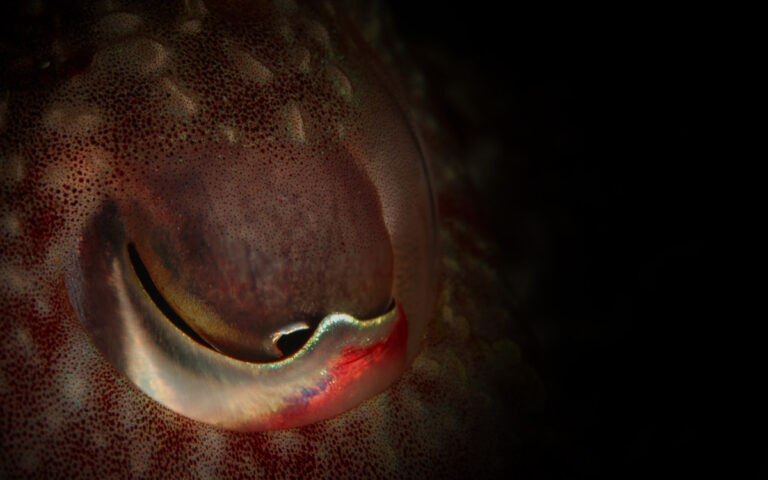

Don’t be fooled by their cute facade, these strange-looking sea creatures give off big brain energy—literally—boasting the largest brains among the invertebrate animal kingdom. And recent research clarifies that cuttlefish are able to put these big brains to good use: allowing them to remember what, where and when specific things happened right up to their final days of life.

The cephalopods, which somewhere down the evolutionary line share the same ancestors as octopi and squid, have three hearts, eight arms, bluish-green blood and regenerating limbs. You wouldn’t be blamed for thinking they’ve been manifested in the imagination of a sci-fi novelist. But they’re not—they’re very much real and even have the ability to exert self-control.

The human brain and the cuttlefish brain

And it’s for this reason that these particular animals have been the focus of scientists’ attention for some time. The University of Cambridge’s recent breakthrough has further pricked their ears. Scientists observed that as the creatures grow older, they show signs of declining muscle function and appetite but appear to remember what they ate, as well as where and when, using this knowledge to guide their future feeding decisions.

The importance of this study becomes clear when contrasting the cognitive behaviour of cuttlefish to humans. In contrast to humans, who gradually lose the ability to remember experiences that occurred at a particular place and time with age, cuttlefish are able to consistently recall such experiences. This is called episodic memory—the ability to recall and mentally re-experience specific episodes from one’s personal past. For instance, what you ate for lunch last week. Its deterioration in humans is linked to a region of the brain called the hippocampus. Cuttlefish, however, don’t possess a hippocampus in their alien-looking heads. Instead, they learn and remember experiences through a part of their brain called the ‘vertical lobe’.

How did they actually study the cuttlefish?

In the study, Doctor Alexandra Schnell, as well as her colleagues, tested the memories of 24 cuttlefish, 12 of which were 10 to 12 months olds and 12 of which were 22 to 24 months old—in cuttlefish years, half would be teenagers and half would be pensioners. One experiment trained both groups of cuttlefish to approach a specific location in the tank they were kept in, with two different foods being provided at different times. Grass shrimps—a cuttlefish’s favourite cuisine—were provided at a different spot to the location they were originally taught to find food but only every three hours. After around four weeks, the molluscs learnt that if they waited for longer they would be rewarded with that sweet, sweet grass shrimp.

To rule out that the cuttlefish hadn’t just learned a pattern of behaviour and were actually using their episodic memory, the team of researchers picked different locations in the tank each day of the test, showing that the molluscs were able to recall the experience—not just act out of habit. The animals also recalled what they ate during the initial feed, where they ate it and how much time had passed.

Although these findings may seem somewhat trivial at face value, they have significant worth for our understanding of animal cognition and our own cognition too. Malcolm Kennedy, professor of natural history at the University of Glasgow, told The Guardian that it’s refreshing to come across another case where aspects of animal cognition can be as advanced as our own—despite huge evolutionary time separation and a different nervous system. He continued, “The pedestal upon which humans place themselves in terms of neurological abilities continues to crumble. It is just that other types of animals perform similar functions differently.” Maybe it’s time we humans start respecting other creatures that share our planet as such.