From frugality to functionality, here’s why barns are painted red

You’ve seen it on Gravity Falls and Phineas and Ferb. You’ve giggled at it on Shaun the Sheep and Sesame Street. Chances are, you’ve even confused the Bagge Farmhouse from Courage the Cowardly Dog with this piece of architecture. Yes, we’re talking about barns today. More specifically, we’re here to solve one of life’s most enduring mysteries: why are barns painted red?

The red barn conundrum

Before we get into the practical and scientific reasons backing the choice of colour, let’s look at some of the fancy guesswork humanity has done in the past. Some people believe red is part of a farmer’s starter pack to aesthetics. Sure, the colour brightens up the landscape when placed against lush vegetation and rusted tractors—you can almost visualise this imagery on a kindergarten desk with strewn crayons. However, spoiler alert: red is actually more than just a choice of paint.

On the one hand, there are some who believe the colour is mandated by law and is chosen to aggravate bulls while keeping them distracted. On the other hand, others argue that the popularity of red barns came from the influence of Scandinavian farmers, who used to douse their properties in the rusty hue to resemble bricks—a material considered to be a sign of wealth back in the day.

Heck, a tiny segment of humans also believe that red barns can help cows find their way home. Cattle are colourblind to red and green, by the way. Two of the most important colours in their life are perceived in tint and tones of grey.

View this post on Instagram

A rusty tradition

So how did the practice of painting barns with the rusty hue begin? And how did this translate into a full-blown tradition as distinct to America as apple pie? Let’s head to the 1700s, back when English settlers in American colonies were setting up new farms, shall we?

During the late 1700s and early 1800s, barns on family farms were typically covered with thick, vertical boards and—surprise, surprise—were left unpainted altogether. Taking temperature, sun exposure, wind and water drainage patterns into account, early builders used to place barns in strategic locations and season the wood by reducing its moisture content accordingly. The treated wood seemed to do the magic without the need for any paint.

In the mid-1800s, farmers wanted to improve the efficiency of their barns by reducing winter drafts to help keep their animals more comfortable. As a result, they nailed wooden clapboards horizontally onto the outside walls of the structure. These boards were sawed quite thin and needed some sort of external protection. Plus, the mentally-intensive method of barn planning from scratch needed a quicker and easier replacement that could guarantee preservation.

In comes the homemade mixture of skimmed milk, lime and red iron oxide which resulted in a plastic-like coating that hardened over wood and extended its lifespan. When farmers added linseed oil from flax plants into the mixture, it boosted absorption, killing fungi and moisture-trapping moss which essentially caused the decay. The oil sealant was pigmented in a burnt-orange red rather than the fire-engine ones that we see today. This is probably why some of the people used to believe that wealthy farmers used to add blood from a recent slaughter into the mixture.

Dubbed ‘Venetian red’, the colour was considered “suitable for any common work, or for brickwork and outbuildings.” The pigment penetrated well into the wooden boards and attracted sunlight—all the while resisting fading and aging gracefully over the years.

View this post on Instagram

By the late 19th century, chemically-pigment paints were mass produced and readily available. Lo and behold, red turned out to be the least expensive colour one could afford to paint massive structures. In 1992, a Sears Roebuck and Co catalogue listed red barn paint for just $1.43, while other colours were sold for at least $2.25 per gallon. Therefore, the colour grew on farmers—up until a brief moment when whitewash became the frugal option of choice and white barns started popping up across the country. “White barns were also common on dairy farms in some parts of Pennsylvania, central Maryland and the Shenandoah Valley,” Mental Floss noted. “Possibly because of the colour’s association with cleanliness and purity.”

At the same time, however, barns in Appalachia—a historically poorer region—remained unpainted for the lack of money. Black and brown barns were additionally preferred in the tobacco regions of Kentucky and North Carolina since the colours helped heat the infrastructure and cure tobacco. Although a decent number of barns still stick to their ancestral choice of paints, red is still dominating the Northeast and Midwest.

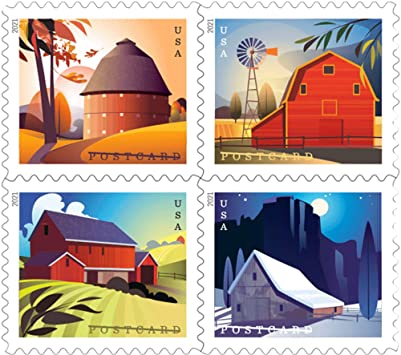

Today, linseed oil is sold as a wood sealant in most home improvement stores. Large barns housing hundreds of cows and pigs also resemble metal hangars and warehouses rather than the classic versions of the infrastructure. But the tradition continues to be honoured and celebrated on everything down to official postage stamps by the US Postal Service (USPS).